History & Nostalgia

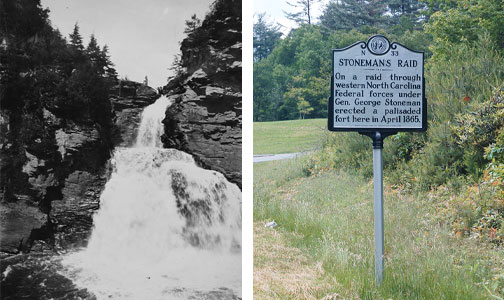

Left: An early 1900s image of Linville Falls taken by Frank Bicknell (State

Archives of North Carolina). Right: There are several state highway historic markers for Stoneman’s 1865 raid, including this one near the fort at Deep Gap. (Michael C. Hardy)

Hardy on History: Hidden History of the Blue Ridge Parkway

By Michael C. Hardy

A popular destination since it partially opened in 1936, the Blue Ridge Parkway (BRP) is visited by millions of visitors every year. They come to see the long-range views, hike the trails, and enjoy the cool summer breezes. Yet the history along the BRP goes back much further than the 1930s. This history includes ties to the American Revolution, the Civil War, and even to an earlier scenic road; much of that history lies hidden in the thick underbrush.

The Blue Ridge Parkway was designed to connect the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee. In a revised plan, instead of turning west in Linville, the Parkway continued to follow the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains, staying on the North Carolina side and never entering Tennessee. The route was surveyed, and local property owners learned that their land was being acquired through eminent domain by the government when notices were posted at the courthouse. Today, the BRP is 469 miles long. Every mile is marked by a concrete post. Those markers, running north to south, correspond with the list below.

276.4 – Deep Gap (Watauga County) | An old road, sometimes referred to as the Old Buffalo Road, crossed through the mountains at the point. The road headed toward Meat Camp, a long hunters’ camp that Daniel Boone visited. In April 1865, Federal soldiers constructed a fort at the site, protecting the lines of communications for Maj. Gen. George Stoneman’s command as he raided through North Carolina and Virginia. Elements of the fort were still visible when the BRP was constructed in the 1930s. The ramp from US 421 to the BRP destroyed most of the fort.

285.1 – Boone’s Trace Overlook (Watauga County) | Daniel Boone was one of the first folk heroes in American history. Born in 1734 in Pennsylvania, Boone migrated with his family, first to Virginia, and then to the Yadkin River Valley in North Carolina. In the 1760s, Boone crossed over the mountains through a gap nearby, hunting for months on end in the Watauga River and Toe River Valleys. The nearby town of Boone is named for the famed hunter. He often stayed at Benjamin Howard’s cabin and was guided by Howard’s slave, Burrell. A bronze marker was once on a boulder at this pull-off denoting the importance of the site.

294 – Moses H. Cone Manor House (Watauga County) | Known as the “Denim King,” Moses Cone operated a textile mill in Greensboro. He and his wife Bertha purchased and developed this property, consisting of 3,600 acres, known as Flat Top Manor. The house was 14,000 square feet, modest compared to other wealthy summer retreats. The Cones also constructed an extensive road network, along with houses for their servants, tennis courts, a croquet lawn, and two lakes. Added to this were extensive apple orchards and herds of sheep and cows. The Cones hired local people to help tend the orchards and pastureland. Moses died in 1908, and Bertha continued to manage the property until her death in 1947. Both are interred on the grounds. Bertha was decidedly against the government taking her property for the BRP, even going so far as writing to President Roosevelt. After her death, the property was transferred to the Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital in Greensboro, who then gave the property to the National Park Service. Most of the buildings on the estate were torn down. Flat Top Manor was considered for a restaurant, or even for demolition. In 1951, the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild opened a craft center in the manor house.

296.5 – Boone Fork Trail (Watauga County) | Located within the Julian Price Memorial Park, the Boone Fork Trail has lots of hidden history. The trail starts in an ancient riverbed. Nearby are caves that once sheltered ancient Native Americans and maybe Civil War dissidents like Keith and Maline Blalock. Part of the trail follows the path of Boone Fork, named for Jesse Boone, a nephew of Daniel Boone. Once leaving Boone Fork, the trail follows an old railroad grade road, carved out over 100 years ago by logging trains from nearby Shulls Mill. And then there is the park’s namesake, Julian Price. He was the founder of the Jefferson Standard Insurance Company, and, after his death, the company donated this property in his honor.

304.4 – Linn Cove Viaduct (Avery County) | For decades the BRP was unfinished. The government wanted a high route on the slopes of Grandfather Mountain. Property owner Hugh Morton refused. Over the years, Morton, the state of North Carolina, and the Federal government wrangled over the route. In the 1970s, a compromise was reached. A middle route was agreed upon, and to protect the boulder field that the BRP would pass through, a bridge was constructed. The Linn Cove Viaduct was completed in 1983. Made up of 153 segments, each weighing fifty tons, it is 1,243 feet long. It has been designated a National Civil Engineering Landmark.

312.2 – Access to NC181 (Avery County) | In the midst of the Civil War, a group of raiders passed through the gap here, on their way to Camp Vance, near Morganton. The late June 1864 raid was led by Capt. George W. Kirk, a Tennessee Unionist. His small band was able to capture the camp and about 250 Junior Reserves. These 16- to 17-year-old boys were in the process of being mustered into the Confederate army to serve as guards when the raid took place. During one of the skirmishes that occurred as Kirk returned through the mountains, some of the Junior Reserves were used as human shields. Kirk and some of his captives were able to return to Tennessee.

316.4 – Linville Falls Recreation Area (Avery and Burke Counties) | Linville Falls might just be the richest history spot along the entire BRP. The Cherokee, who had seasonal hunting camps in the area, called the falls and river Eeseeoh, “the river of many cliffs.” The area was declared off-limits to settlers by King George III in 1763. In 1766, William Linvil [Linville], his son, and another man were hunting in the area when they were attacked by a “Northern band” of Indians, possibly Shawnee. The two Linvils were killed, but gave their name to the river, falls, and several communities in the area. During the Civil War, there was a camp here to process iron ore mined locally. The camp was attacked, possibly by Kirk’s men. In the early 20th century, there were tourist homes and a sawmill along the river. In 1951, philanthropist John D. Rockefeller donated $95,000 to the National Park Service to acquire hundreds of acres in the area, including Linville Falls.

328.6 – The Loops Overlook (McDowell County) | Near the historic Orchard at Altapass are the Clinchfield Loops, sections of railroad constructed between 1905 and 1908. The railroad was built to connect the coalfields of Kentucky with the cotton mills in central North Carolina and South Carolina. To help the heavy trains navigate the steep grade, a series of eighteen tunnels and numerous switchbacks were built. Some of the workers brought in were Italian immigrants seeking to escape poverty in Italy. In May 1906, in a workers’ camp near this location, a riot broke out between the sheriff and workers. The workers were upset over not getting paid. At least two Italians were killed. Also near this location, running for several miles along the BRP, are the remnants of the Crest of the Blue Ridge Highway. Plans were for this scenic highway to stretch from Marion, Virginia, to Tallulah, Georgia. Work began on this section in 1914. The road was twenty-four feet wide, with a sand or gravel surface. World War I halted construction. Remnants can be viewed in the fall in the woods on the north side of the BRP.

330.9 – North Carolina Museum of Minerals (Mitchell County) | The Toe River Valley is one of the richest areas, minerally speaking, in the United States. And the North Carolina Museum of Minerals, which opened in 1955, is a great place to explore this history. However, there is more hidden history. The museum is located at Gillespie Gap. In September 1780, militiamen from the Watauga Settlements, and from Virginia, camped near here on their way to Kings Mountain to fight the British under Maj. Patrick Ferguson. Thomas Jefferson considered the battle, a Patriot victory, the turning point of the American Revolution.

Although these spots along the Blue Ridge Parkway may be largely hidden, they represent important glimpses into the past and into our history.